Sometimes a seizure happens so quickly that your mind has to play catch-up. One moment you’re assessing your patient, and the next you’re rewinding the scene in your head, trying to lock in every detail you’ll need for the chart.

In this guide, you’ll find seizure nursing documentation examples that make the process easier and more predictable. We’ll walk through what to document before, during, and after a seizure, using clear steps, real-world notes, and table-style templates based on what nurses actually use at the bedside.

What Is Seizure Documentation?

Seizure documentation is the structured record of what happened before, during, and after a seizure. It’s a clinical timeline that helps the healthcare team understand the event with clarity. When done well, it becomes one of the most valuable pieces of information in a patient’s neurological history.

Why Seizure Documentation Matters in Nursing

A seizure can look different from one person to the next. Some are loud and obvious; others are subtle and easy to miss. That’s why your documentation becomes a bridge between what you witnessed and what the provider needs to know.

Here’s what accurate seizure documentation supports:

- Diagnosis: Providers rely on detailed accounts to determine the seizure type.

- Medication decisions: Anti-seizure drug adjustments often depend on your note.

- Tracking patterns: Small details help identify triggers like stress, flashing lights, lack of sleep, fever, missed meds, or infections.

- Safety planning: Documentation helps tailor seizure precautions to the patient’s real needs.

Legal and Safety Benefits

Accurate seizure documentation also protects you and your patient.

- It shows you assessed promptly.

- It proves you provided safe intervention.

- It supports incident reports and care plan updates.

- It ensures continuity when the next nurse takes over.

Think of the documentation as both a clinical tool and a safety net. It captures what happened, what you did, and what the patient needed next.

For more on Nursing documentation check out our article on Good nursing notes

What Nurses Should Document Before, During, and After a Seizure

Seizure documentation works best when you follow a simple sequence: before → during → after.

This structure keeps your note organized, reduces guesswork, and makes it easy for providers to understand what happened.

Let’s break each phase down.

What to Document Before the Seizure

What happens before the seizure often gives important clues about triggers, aura symptoms, and environmental factors. This is the part many nurses skip — but it’s gold for neurologists.

Key details to capture

- Patient activity: What they were doing before the seizure started

- Walking, eating, resting, turning in bed, using the bathroom, in class, etc.

- Walking, eating, resting, turning in bed, using the bathroom, in class, etc.

- Possible triggers:

- Stress, flashing lights, fever, missed medication, infection, sleep loss

- Stress, flashing lights, fever, missed medication, infection, sleep loss

- Environment:

- Was the room noisy? Crowded? Bright? Safe?

- Was the room noisy? Crowded? Bright? Safe?

- Aura or prodromal signs:

- Strange smells or tastes

- Sudden fear, anxiety, or irritability

- Dizziness or nausea

- Déjà vu

- Tingling or numbness

- Visual or auditory changes

- Strange smells or tastes

These details come from clinical guidance found in patient-education sources like Medical News Today and neurological research that highlights the importance of pre-seizure symptoms.

What to Document During the Seizure

This is the most critical part of your note.

Try to observe without touching unless safety becomes an issue.

Essential details

- Start time: The very first change you noticed

- Duration: Use a timer if possible

- Level of consciousness:

- Aware, partially aware, or unresponsive

- Aware, partially aware, or unresponsive

- Movements:

- Jerking, stiffening, twitching, or automatisms (like lip-smacking)

- Jerking, stiffening, twitching, or automatisms (like lip-smacking)

- Body parts involved:

- Left side, right side, both sides, or generalized

- Left side, right side, both sides, or generalized

- Eyes:

- Open, closed, deviated to one side, or rolled back

- Open, closed, deviated to one side, or rolled back

- Breathing:

- Normal, shallow, gasping, or paused

- Normal, shallow, gasping, or paused

- Skin color:

- Pale, flushed, cyanotic

- Pale, flushed, cyanotic

- Incontinence:

- Urinary or bowel

- Urinary or bowel

- Injuries:

- Fall, tongue biting, head strike, scrapes, bruising

- Fall, tongue biting, head strike, scrapes, bruising

These points reflect guidance from seizure observation tools and clinical resources such as Lecturio and health-environment safety guides.

What to Document After the Seizure

The post-ictal phase can tell you as much as the seizure itself. Some patients bounce back quickly. Others struggle for minutes or even hours.

Important observations

- Recovery time:

- Note how long it takes for the patient to respond or follow commands

- Note how long it takes for the patient to respond or follow commands

- Orientation:

- Do they know their name, location, or date?

- Do they know their name, location, or date?

- Vital signs:

- Especially respiratory rate and oxygen saturation

- Especially respiratory rate and oxygen saturation

- Pain or discomfort:

- Headache, muscle soreness, tongue pain

- Headache, muscle soreness, tongue pain

- Weakness or fatigue:

- One-sided weakness (Todd’s paralysis) or full-body exhaustion

- One-sided weakness (Todd’s paralysis) or full-body exhaustion

- Mood or behavior changes:

- Agitation, confusion, tearfulness, restlessness

- Agitation, confusion, tearfulness, restlessness

- Memory of the event:

- Many patients have no recall

- Many patients have no recall

- Interventions:

- Oxygen, airway support, blood glucose checks

- Medication given (per order)

- Safety measures

- Provider notified

- Oxygen, airway support, blood glucose checks

Post-ictal documentation aligns with teaching resources like Lecturio and nursing seizure-care plans.

Standard Seizure Documentation Table

| Date & Time | Duration | What Happened Before? | What Happened During? | What Happened After? | Actions Taken | Signature |

| When the seizure started | Length in minutes/seconds | Activity, triggers, aura, environment | Movements, consciousness, breathing, body parts, eyes, injuries | Orientation, vitals, behavior, recovery time | Safety steps, oxygen, meds, provider notified | Initials or full signature |

Seizure Nursing Documentation Examples

Documentation gets easier when you can see what a complete note looks like.

Below are clear, realistic nursing documentation examples you can model in your own charting.

Each one follows the same structure you used earlier: before → during → after → actions taken.

Think of these as templates you can adapt on any shift — simple enough for busy days, detailed enough for good clinical care.

Example 1 – Generalized Tonic–Clonic Seizure (Adult, Med-Surg)

Table Format

| Date & Time | Duration | Before | During | After | Actions Taken | Signature |

| 02/12/25, 14:18 | 1 min 40 sec | Patient sitting up in bed eating lunch. No reported aura. No known triggers. | Sudden loss of consciousness, tonic stiffening followed by rhythmic jerking of all extremities. Eyes rolled back. Breathing shallow with brief cyanosis around lips. No incontinence noted. | Patient drowsy and confused for ~7 minutes. Oriented to name only. Complained of headache. VS stable. No injuries found. | Bed lowered, side rails padded, O₂ applied at 2 L/min. MD notified. Neuro checks q15 min × 1 hr. | JN |

Narrative Format

At 14:18, patient lost consciousness while eating lunch. No aura reported. Tonic stiffening occurred, followed by rhythmic jerking of all extremities. Eyes rolled back. Breathing became shallow with slight perioral cyanosis. No incontinence noted. Seizure lasted 1 min 40 sec.

Post-ictal: Patient was drowsy and confused for about 7 minutes. Oriented only to name. Complained of headache. Vital signs stable. No injuries found. O₂ applied at 2 L/min via nasal cannula. Provider notified. Neuro checks continued per protocol.

Example 2 – Focal Impaired Awareness Seizure (Neuro Unit)

Table Format

| Date & Time | Duration | Before | During | After | Actions Taken | Signature |

| 02/12/25, 09:52 | ~55 sec | Patient watching TV. Reported “weird taste” moments before event. | Sudden blank stare, lip-smacking, right-hand picking movement. Unresponsive to verbal questions. Eyes open and deviated slightly left. No cyanosis. | Patient regained awareness slowly, appeared confused for 3 minutes. No memory of event. | Ensured safety, stayed at bedside, documented movements. Provider notified. | JN |

Narrative Format

Patient reported a “weird taste” at 09:51. At 09:52, patient developed a blank stare with lip-smacking and right-hand picking motion. Unresponsive to verbal cues. Eyes deviated slightly to the left. Breathing even. No incontinence.

Seizure lasted ~55 seconds. Patient regained awareness slowly with mild confusion for 3 minutes. No memory of event. Provider notified for follow-up evaluation.

Example 3 – Pediatric Seizure at School (School Nurse Documentation)

Table Format

| Date & Time | Duration | Before | During | After | Actions Taken | Signature |

| 02/12/25, 11:23 | 1 min 10 sec | Student in classroom reading quietly. Teacher noted student rubbing eyes repeatedly. | Student suddenly became still, then began full-body stiffening followed by jerking of arms and legs. Eyes open. No breathing pause noted. No injury. | Student sleepy and tearful after event. Oriented to name and teacher but not to time. | Placed student on side for safety. Called parents. Followed student’s seizure action plan. EMS not required. | LN |

Narrative Format

At 11:23, student experienced full-body stiffening followed by rhythmic jerking lasting 1 min 10 sec. No fall or injury occurred. Breathing remained steady. Post-ictal period marked by fatigue and tearfulness. Student oriented to name and teacher.

Side-lying position maintained throughout. Parent contacted. School seizure action plan followed. Student remained in nurse’s office for monitoring.

Example 4 – Post-Seizure Nursing Documentation Example

Table Format

| Date & Time (Found) | Duration (Unwitnessed) | Before | During | After | Actions Taken | Signature |

| 02/12/25, 04:10 | Unwitnessed | Patient last seen awake at 03:45. No staff observed triggers. | Unwitnessed. Patient found lying on side, diaphoretic, confused. Small bite mark on left tongue. | Confused × 12 minutes. Slowly regained orientation to person and place. Mild headache and left-arm weakness noted. | Checked vital signs and blood glucose. Ensured airway patency. MD notified immediately. Neuro checks initiated. | JN |

Narrative Format

Patient found at 04:10 lying on left side, diaphoretic, confused, and responsive only to voice. Small tongue bite noted. Seizure unwitnessed. Patient was last observed awake at 03:45. Post-ictal confusion lasted 12 minutes. Mild left-arm weakness and headache reported. Airway patent. Vitals stable. Glucose checked. Provider notified. Neuro checks continued.

Example 5 – Absence Seizure (Pediatric)

Table Format

| Date & Time | Duration | Before | During | After | Actions Taken | Signature |

| 02/12/25, 10:14 | 12 seconds | Student sitting at desk during math activity. No reported triggers. | Sudden staring spell, unblinking eyes, slight eyelid fluttering. Unresponsive to name. No movement of limbs. | Returned to activity immediately with no confusion. No memory of event. | Documented episode. Informed parent and teacher. Monitored for recurrence. | LN |

Narrative Format

At 10:14, student had a brief staring episode lasting about 12 seconds. Eyelids fluttered slightly. Unresponsive during event but maintained posture. No color change or motor involvement. Returned to normal behavior immediately. No post-ictal confusion. Parent notified for follow-up with pediatric provider.

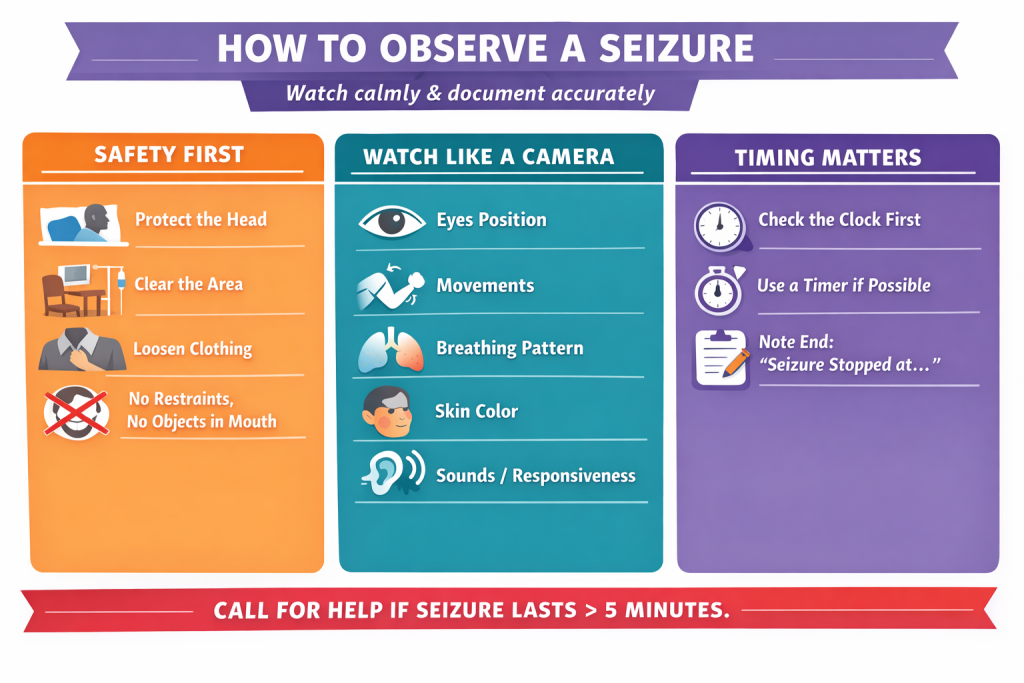

How to Observe a Seizure

Observing a seizure isn’t about staring — it’s about staying calm, keeping your patient safe, and noticing details that matter later when you chart. The more structured your observation, the easier the documentation becomes.

Think of this as your bedside checklist. Simple. Clear. Repeatable.

Safety First

Your first job is always safety. Not documentation. Not analysis.

Focus on:

- Protecting the head

Slide a pillow or folded blanket under the head if possible. - Clearing the area

Move chairs, bedside trays, IV poles, or anything sharp. - Loosening tight clothing

Especially around the chest and neck. - Never restraining the patient

Let the seizure run its course. - Never putting anything in the patient’s mouth

Old myths still float around — ignore them.

A safe environment gives you space to observe without interfering.

What to Watch For (Structured Observation)

If you’re able to safely observe, this is where your future documentation comes from.

Try to watch like a camera: objective, simple, detail-focused.

Eyes

- Open, closed, rolled back, or deviated to one side

Limb movements

- Jerking

- Twitching

- Stiffening

- Repetitive movements (like picking or lip-smacking)

Breathing

- Normal

- Shallow

- Irregular

- Brief apnea

- Cyanosis around lips or fingertips

Skin color

- Pale

- Flushed

- Blue-tinged

Responsiveness

- Do they react to their name?

- Any purposeful movement?

- Any vocalizations?

Sounds

- Crying out at onset

- Gurgling or choking sounds

- Rhythmic breathing changes

Every detail you notice becomes a building block for your chart later.

Timing & Tools

A seizure may feel long, but our perception is usually wrong in the moment.

This is why timing matters so much.

Tips for accuracy

- Check the clock the moment you notice changes.

- Use your phone timer if policy allows.

- Note the end time when rhythmic movements stop or the patient relaxes.

- If you arrive mid-seizure, chart “seizure in progress upon arrival”.

Clear timing helps identify seizure type and decide if emergency medications are needed.

When to Escalate

Some seizures require immediate action.

If you see any of the following, escalate without delay:

Call for help if:

- The seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes

- The patient has back-to-back seizures without waking up

- Breathing does not return to normal afterward

- The patient is injured during the event

- It’s the first seizure for this patient

- You’re unsure whether the episode is epileptic or another medical emergency

Trust your clinical judgment. If something feels off, it’s better to escalate.

FAQs – Seizure Nursing Documentation

Every nurse has questions about seizure documentation — especially when events happen fast and the chart needs to be precise. These short answers will help you document with more clarity and confidence.

What is the most important thing to chart first during a seizure?

The start time.

It’s the single most important detail because it guides every medical decision that follows — from medication orders to emergency escalation. A seizure that lasts more than 5 minutes becomes a medical emergency, so timing matters.

If you didn’t see the exact start, write something like:

- “Seizure observed in progress at 14:32; start time unknown.”

This keeps your documentation accurate and honest.

How detailed should seizure documentation be in nursing?

Aim for clear, factual, and concise.

You don’t need long sentences. You don’t need to describe emotions or assumptions. You just need the clinical facts:

- What you saw

- How long it lasted

- What the patient looked like

- What you did

A good rule: document enough detail that another nurse could visualize the event clearly.

Do I document aura or just seizure activity?

Document both.

An aura often shows the seizure’s origin in the brain, especially in focal seizures. It can include:

- Smells

- Tastes

- Sudden fear

- Deja vu

- Tingling

- Visual changes

Even when it seems small, aura information helps neurologists classify the seizure and fine-tune treatment.

How do I document if I didn’t witness the seizure?

Use the structure, but state clearly that the event was unwitnessed.

Here’s a simple example:

- “Patient found lying on right side, confused. Tongue bite noted. Seizure unwitnessed. Last known well at 03:50.”

If someone else saw the event (another nurse, a visitor, a teacher), include their report in objective language:

- “Per teacher report: student became stiff, then had rhythmic jerking of arms.”

Never guess or estimate. Just record what you observed directly and what was reported to you.

How many seizures should go on one seizure log sheet?

Most seizure logs use one event per row or one event per page depending on the format.

For clinical units, the rule is:

- One seizure = one complete entry

For school settings or long-term care:

- Daily logs may include multiple seizures on one sheet, but each event still needs its own row or box with start and end times.

If you’re unsure, follow your facility’s seizure documentation policy.