Giving a patient handover can feel nerve-wracking. You have a lot of information in your head, and you need to get it out clearly and quickly. However, with the right structure, you can turn that anxiety into confidence.

This guide provides 10 ISBAR examples for nursing students. These are designed to help you navigate clinicals, exams, and real-life emergencies with ease.

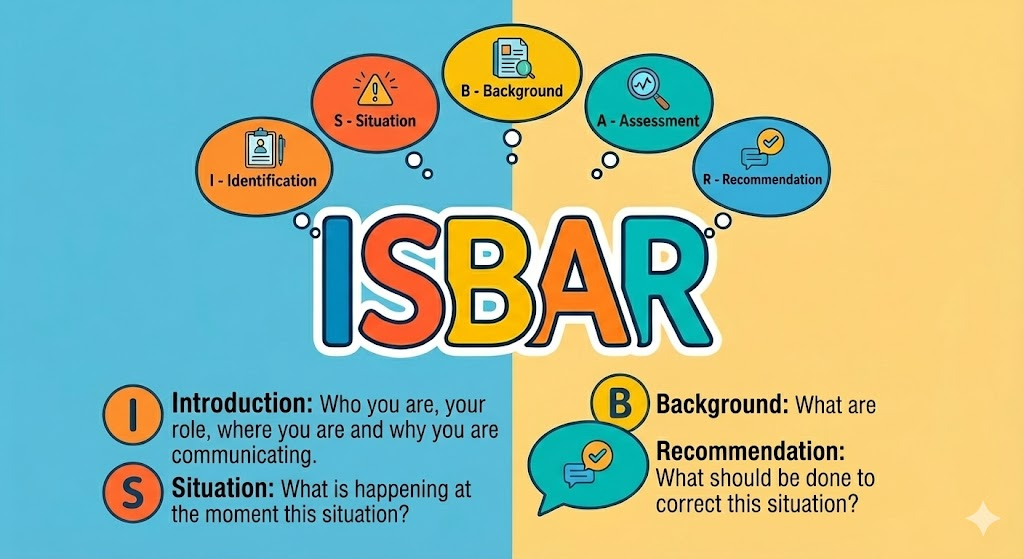

What Is ISBAR and Why Does It Matter?

ISBAR is a lifeline for communication in the hospital. It stands for:

- Identify

- Situation

- Background

- Assessment

- Recommendation

It gives you a solid framework to deliver clear updates that keep patients safe. Interestingly, this system was originally used by military pilots. Hospitals adopted it to stop communication errors—which are a huge cause of mistakes in healthcare.

A Quick Breakdown of the ISBAR Structure

Let’s look at how the pieces fit together.

I – Identify

Start by saying exactly who you are and who the patient is. This grounds the conversation immediately.

- Example: “Hi, I’m Aisha, a student nurse. I’m calling about Mr. John Carter in Room 12B.”

- Why it matters: Mixing up patients is a common mistake. Always start here, even if you are in a hurry.

S – Situation

What is the headline news? Explain the immediate problem directly. Imagine someone asking, “Why are you calling me right now?”.

- Example: “He has a fever of 39.2°C and is shivering.”

- Note: If you aren’t sure what is wrong, just say, “I’m concerned.” Honesty is better than guessing.

B – Background

This is the backstory. You don’t need their whole life history—just the parts that matter for this specific problem.

- Example: “Mr. Carter came in yesterday with a UTI. He also has Parkinson’s and takes Warfarin.”

- Tip: Think “useful,” not “long”.

A – Assessment

This is where you use your brain. Share your vital signs and what you think is going on.

- Example: “His BP is low (88/52) and he looks flushed. I’m worried this might be sepsis.”

- Tip: It is okay to ask for help here. Confidence means knowing when to escalate the situation.

R – Recommendation

Finish with a clear plan. What do you need the doctor or team to do?.

- Example: “Can you please come see him now? I think we should start antibiotics.”

- Tip: This turns your report into a call to action.

10 ISBAR Examples for Nursing Students

1. Post-Operative Orthopedic Patient

Scenario: You are handing over a patient who just had a hip replacement.

“Hi, this is Daniel Roberts (check wristband), DOB 22/06/1954.

Situation: He was admitted yesterday after a fall and breaking his hip. He is now Day 1 after a total hip replacement.

Background: He has a history of atrial fibrillation (he takes Warfarin), high blood pressure, and mild COPD. He is allergic to penicillin.

Assessment: His pain is under control with paracetamol and oxycodone. His vital signs are stable, and the dressing is dry. He is moving around with the physio team using a frame.

Recommendation: He is just waiting for his post-op X-ray. Once that is done, we can start discharge planning. Do you have any questions?”

2. Pediatric Asthma Exacerbation

Scenario: A child is admitted with breathing difficulties, and you need a doctor to review them.

“This is Lily Nguyen (check ID band), DOB 15/03/2014.

Situation: She was admitted this morning for a severe asthma flare-up.

Background: She has had asthma since age 3 but hasn’t needed the hospital in the last year. She has no allergies. She has had three nebulizers in 6 hours.

Assessment: She still has a moderate wheeze and is working hard to breathe. Her oxygen is 93% on 2L, heart rate is 110, and breathing rate is 26. Her parents are here with her.

Recommendation: We are waiting for the respiratory team to decide on oral steroids. Would you like me to get the medication ready now?”

3. Elderly Patient with UTI and Delirium

Scenario: An older patient is confused, and you are handing over to the next shift.

“This is Margaret Kelly (check wristband), DOB 08/12/1932.

Situation: She came in 2 days ago with confusion and wasn’t eating. She is being treated for a UTI.

Background: She has dementia and arthritis. She is allergic to codeine. We started her on IV antibiotics.

Assessment: She is still showing signs of delirium, especially at night. Her vitals are stable (BP 138/74), and she has no fever. She needs help walking and with continence care.

Recommendation: She is waiting for an Occupational Therapy review. Do you have any concerns before I head out?”

4. Mental Health – Suicidal Ideation

Scenario: A patient has disclosed a plan to harm themselves, and you need to ensure safety.

“This is Darren Price, DOB 04/04/1992.

Situation: He is a voluntary admission for major depression. Today, he admitted he has suicidal thoughts with a vague plan to overdose.

Background: He has a history of self-harm but no past suicide attempts. He is not eating well and is very withdrawn.

Assessment: His vitals are stable, but he is currently on 1:1 observation to keep him safe.

Recommendation: A psychiatry review is booked for 9 a.m. tomorrow. Please keep checking his safety and ensure his belongings are locked away. Do you have any questions about his risk management?”

5. Palliative Care – Pain Management

Scenario: You are caring for a patient at the end of life, focusing on comfort.

“This is Helen Carter, DOB 10/10/1949.

Situation: She is here for symptom control for advanced ovarian cancer. We are following a palliative care pathway.

Background: She has high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. She is on a continuous morphine infusion, which is working well.

Assessment: She is stable and comfortable with no signs of distress. She is eating small meals, and her family is visiting often.

Recommendation: The plan is to continue comfort care and emotional support. Is there anything you need to ask before taking over?”

6. Emergency Department – MVC Trauma

Scenario: A patient just arrived after a car crash. You need to update the trauma team while waiting for scans.

“This is Michael Stone (check wristband), DOB 05/01/1985.

Situation: He came in 2 hours ago after a high-speed car crash.

Background: He has no past medical history and no allergies. We have started IV fluids and given him pain relief.

Assessment: His GCS is 15 (he is alert), but he is complaining of stomach pain and weakness in his left leg. His blood pressure is low (94/62), and his heart rate is high (118).

Recommendation: We are waiting for a CT scan of his abdomen and pelvis. Is there anything else you want to clarify about his management right now? “

7. Maternity – Postpartum Hemorrhage Risk

Scenario: A new mother is bleeding heavily after giving birth. This is an urgent situation.

“This is Sarah Adams (check ID), DOB 18/07/1996.

Situation: She gave birth to a healthy baby boy 3 hours ago. My current concern is heavy bleeding and a ‘boggy’ (soft) uterus.

Background: She has O negative blood and no allergies.

Assessment: She is soaking a pad every 10 minutes. Her heart rate is 112, and BP is 88/54. We have IV oxytocin running.

Recommendation: I need an urgent obstetric review. Would you like me to prepare for a manual removal of the placenta? “

8. Surgical Ward – Suspected Sepsis

Scenario: A patient recovering from an appendectomy has a sudden fever. You suspect an infection.

“This is Anita Kumar (check wristband), DOB 02/05/1988.

Situation: She is Day 2 after having her appendix removed.

Background: She has mild asthma but no drug allergies.

Assessment: She has a high fever (39.4°C), low BP (86/50), and a fast heart rate (124). Her surgical wound looks red and tender. I have taken blood cultures and started fluids.

Recommendation: I need an urgent review by the surgical registrar. Do you need any more details before you take over? “

9. Cardiac Ward – Chest Pain

Scenario: A heart patient reports new chest pain. You need to escalate this quickly.

“This is Robert Lee, DOB 09/11/1955.

Situation: He was admitted yesterday with angina (chest pain). He reported feeling chest pressure 20 minutes ago.

Background: He has a history of heart disease and had a stent put in last year. He is on aspirin.

Assessment: His ECG shows changes (ST depression). His BP is 92/60 and heart rate is 104. I have put him on oxygen.

Recommendation: We are waiting for cardiology to see him. Do you want me to prep him for a transfer to the cath lab? “

10. Pediatric Ward – Post-Tonsillectomy Care

Scenario: A young child can’t keep water down after throat surgery and is getting dehydrated.

“This is Ethan White (check wristband), DOB 11/01/2018.

Situation: He had his tonsils out this morning.

Background: He has no other medical history.

Assessment: He is vomiting and can’t tolerate fluids. His heart rate is 110, and he is showing signs of mild dehydration.

Recommendation: I am waiting for the pediatrician to review him for IV fluids and anti-nausea meds. Do you have any questions about his care? “

Final Thoughts on Using ISBAR Examples for Nursing Students

Think of these ISBAR examples for nursing students as a workout for your brain. The more you practice this language, the clearer you will think under pressure.

These scenarios are perfect for:

- Building confidence before you step into simulation labs.

- Prepping for job interviews or exams.

- Guiding your care plan presentations.

If you ever freeze up during a shift report or a scary moment, just take a breath and go back to the letters: I-S-B-A-R. It is not just about passing a class. It is about learning to lead and advocate for your patients like a pro.

Common Questions Nursing Students Ask about ISBAR.

Q1: What exactly does ISBAR stand for, and why is the “I” (Identify) included?

A: ISBAR stands for Identify, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation. The “Identify” step asks the communicator to introduce themselves, state their role, and clearly identify the patient (e.g. by name, DOB or hospital ID). This ensures clarity — especially in busy settings — preventing mix‑ups between patients or confusion about who is speaking.

Q2: In what situations should I use ISBAR (versus when is it less necessary)?

A: ISBAR is recommended especially during shift handovers, inter‑hospital transfers, intra-hospital transfers (e.g. ward to theatre), discharge to community services, and in urgent or time‑critical situations — such as emergencies or changes in patient condition. It’s also useful for both verbal and written communication (phone calls, referrals, written notes).

However, for very routine updates (e.g. “patient stable, continuing current plan”) the full ISBAR handover may not always be necessary — but many institutions encourage using it as standard to reduce risk of omissions.

Q3: What are the benefits of using ISBAR in clinical practice?

A: Research shows that standardized use of ISBAR improves clarity, consistency, and completeness of clinical handovers. In emergency and acute-care settings, it enhances patient and professional safety, supports continuity and quality of care, reduces risk of information loss during handovers, and boosts confidence among staff giving or receiving reports.

It flattens hierarchy by giving everyone — regardless of seniority — the same structure for communication, which helps avoid misunderstandings.

Q4: Are there common mistakes or pitfalls when using ISBAR?

A: Yes. Some common pitfalls include: giving too much irrelevant background (making the handover too long), omitting key identifiers (patient name, DOB, unit/room), neglecting to summarise a clear recommendation at the end, or failing to prioritise what is urgent. Also, trying to guess a diagnosis rather than clearly stating concerns — better to say “I’m concerned” if unsure. This helps prevent misinterpretation. (This reflects general guidance around structured handover.)

Additionally, busy or chaotic environments (interruptions, noise) can compromise handover quality — using the ISBAR format helps mitigate but doesn’t eliminate that risk.

Q5: Who can use ISBAR — is it only for nurses, or also doctors, allied health, etc.?

A: ISBAR is versatile and can be used by many types of healthcare professionals — nurses, doctors, allied health staff, pharmacy, midwives, even during transfers between facilities or non‑hospital settings. It standardizes communication across disciplines, making sure everyone speaks the “same language”.

Q6: Can ISBAR be used for both verbal handovers and written reports?

A: Yes. ISBAR works for both — whether you are handing over verbally (e.g. at shift change, by phone, or in person) or writing a handover note or referral. Its structured format ensures that essential information is captured clearly regardless of medium.

Q7: Is there evidence that using ISBAR actually improves patient outcomes or reduces errors?

A: Yes. For example, a recent scoping review focused on emergency department handovers found that using ISBAR leads to safer, clearer, and more concise care transitions. This improves patient and professional safety, quality and continuity of care. Also, training staff in ISBAR has shown to increase confidence and perceived communication effectiveness — which can indirectly reduce risk of misunderstandings or omissions.

Q8: How do I prioritise what background or assessment details to include when using ISBAR — especially when time is limited?

A: Focus only on information relevant to the current situation. Include key identifiers, current diagnosis or admission reason, relevant medical history, allergies, medications, vital signs, recent changes, and what you think needs urgent attention. Avoid overloading with full medical/personal history — brevity and relevance are the point of ISBAR. Many ISBAR guides recommend gathering and organising thoughts before delivering the handover (sometimes as bullet‑points) so you communicate clearly and quickly.

Q9: Can ISBAR be adapted — or does it always have to be exactly the 5 components?

A: While ISBAR’s core 5 components are standard and widely accepted, the format can be adapted to the context — for example, for mental health handovers you may include a mental status assessment or risk factors as part of “Assessment” or “Background.” What matters is that the key structure remains: clear identification, situation, relevant background, professional assessment, and recommendation. Many educators encourage tailoring to the patient case while preserving clarity and completeness.

Q10: How can I practice or prepare an effective ISBAR handover when I’m a student?

A: You can use simulation labs, peer‑to‑peer handover drills, or practice with case‑scenarios — ideally diverse ones (postoperative, paediatric, psychiatric, emergency etc.) to reflect real‑world variety. Writing out handover notes using ISBAR in study sessions helps — then try delivering them aloud to refine clarity and brevity. Because ISBAR works for both written and verbal communication, practicing both helps build confidence before real clinical situations.