Ever walked into a patient room and thought, “Okay… who needs me first?” That split second — where your instincts and training collide — is exactly why the ABC of nursing exists. It’s the framework that helps you think fast, stay calm, and focus on what truly keeps a patient alive: Airway, Breathing, and Circulation.

In nursing, chaos is part of the job. Machines beep, family members panic, and patients can go from stable to critical in seconds. The ABCs cut through that noise. They give you a clear order of action — a way to decide, in any situation, what to fix first and what can wait another minute.

This guide breaks down the ABC of nursing examples you’ll actually use in practice — from emergency rooms and post-op units to pediatric wards and maternity care. You’ll learn how to:

- Spot the earliest signs of airway or breathing failure

- Use ABCs to prioritize patients and avoid fatal delays

- Apply related models like ABCDE and CAB in CPR with confidence

Because when everything around you feels urgent, ABCs remind you what truly is.

You’ve cared for patients, helped with homework, and now it’s your turn to face another paper. We get it. Our nursing experts step in so you can rest, refocus, or simply breathe without falling behind.

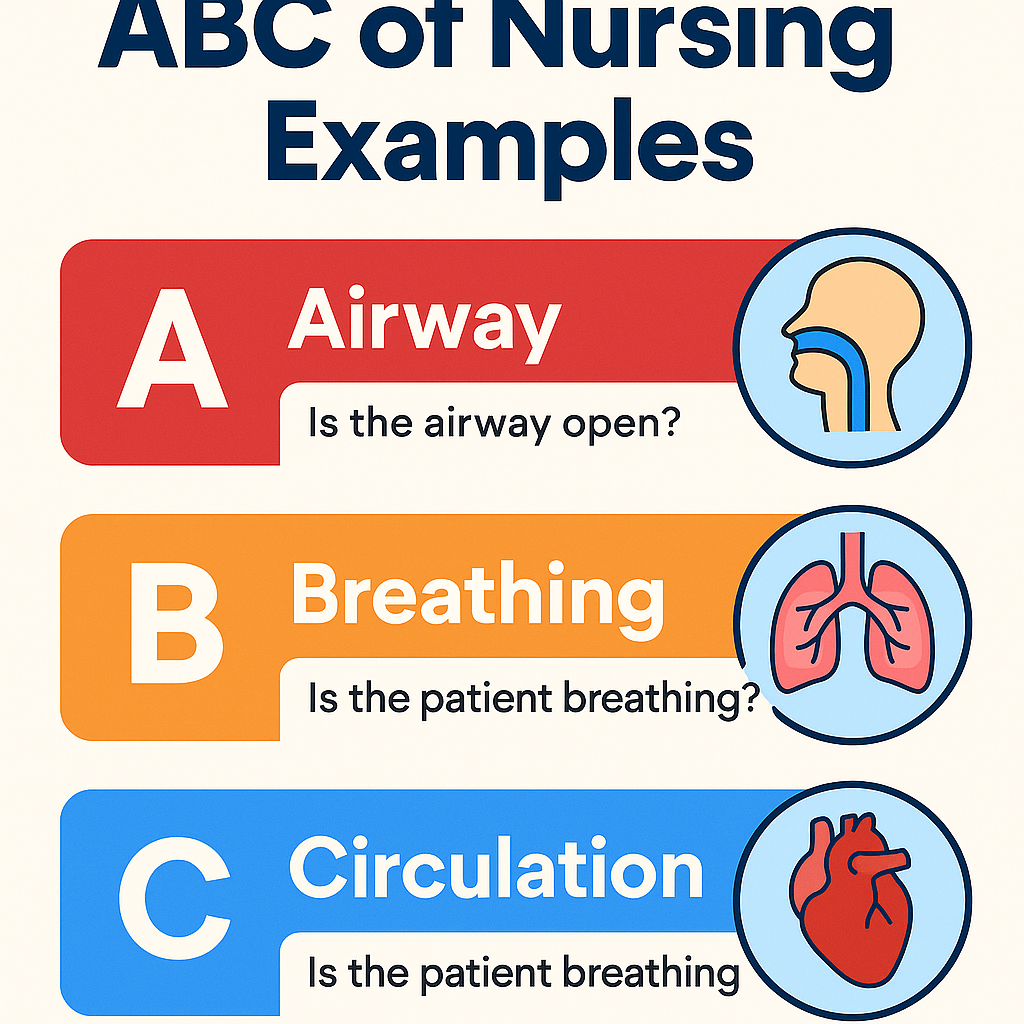

What Is ABC in Nursing?

In nursing, ABC stands for Airway, Breathing, and Circulation — the three essential functions your body needs to stay alive. It’s not just a checklist; it’s the foundation of emergency care and patient prioritization. Every assessment, whether in the ICU or a classroom simulation, starts here.

Let’s break it down simply:

- Airway – This is the pathway that lets air move from the mouth and nose into the lungs. If the airway is blocked — say by food, vomit, or swelling — oxygen can’t even reach the lungs.

- Breathing – This is the actual movement of air in and out of the lungs. It’s how oxygen enters the bloodstream and carbon dioxide leaves. Without effective breathing, even a clear airway won’t help.

- Circulation – Once oxygen enters the blood, the heart must pump it throughout the body. Circulation keeps the brain and vital organs alive by delivering oxygen-rich blood where it’s needed.

Think of ABC like the body’s life-support hierarchy:

If one step fails, everything else collapses. That’s why nurses always ask themselves, “Which one is failing right now — airway, breathing, or circulation?”

Here’s the reasoning behind it:

- If the airway is blocked, oxygen can’t even enter the lungs.

- If breathing stops, oxygen can’t get into the blood.

- If circulation fails, that oxygen never reaches the organs that depend on it — especially the brain.

So, the ABC approach helps you decide what to fix first when a patient’s condition changes. It’s your internal compass in every emergency — from a choking child to a trauma patient or cardiac arrest case.

In short, ABC is triage in motion:

- Airway first.

- Breathing second.

- Circulation third.

Miss one, and nothing else you do will matter. That’s why nurses live by this question:

👉 “What will harm or kill the patient first if I don’t act now?”

ABC Nursing Assessment: Step-by-Step Guide

Before medications, diagnostic tests, or wound care — your first question should always be:

“Is this patient alive and stable?”

The ABC nursing assessment gives you a clear pathway to answer that, even when things feel chaotic.

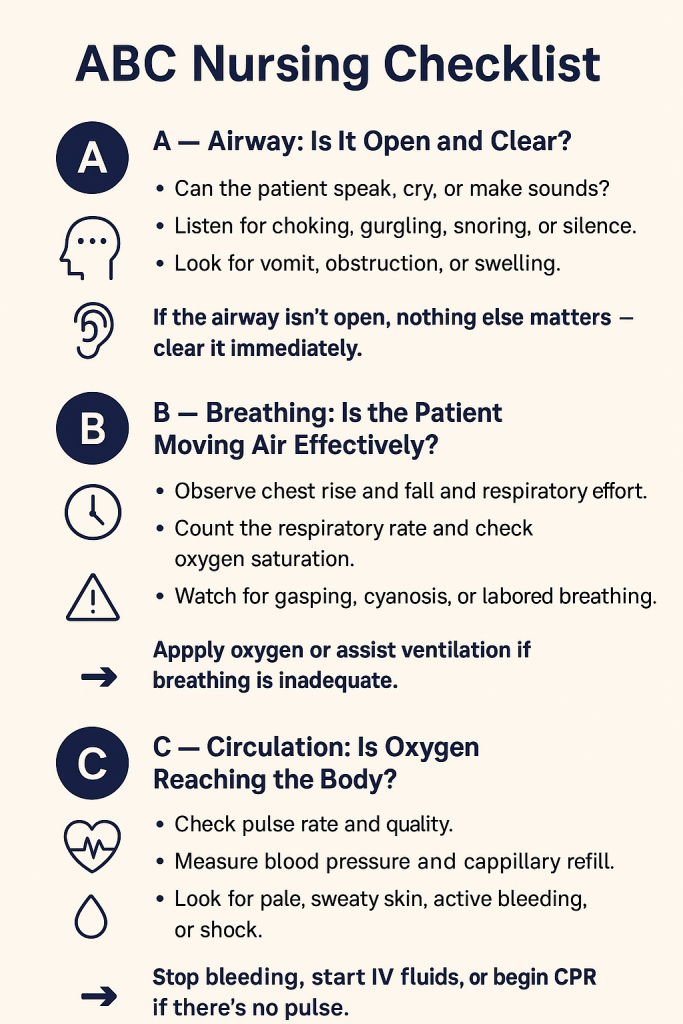

Step 1: Airway — Is It Open?

What to assess:

- Can the patient speak, cry, or make sounds?

- Do you hear choking, snoring, gurgling, or silence?

- Is there swelling, vomit, blood, or the tongue blocking the airway?

What to do first:

- Use a head-tilt–chin-lift to open the airway.

- If trauma is suspected, use a jaw-thrust to protect the cervical spine.

- Suction vomit, blood, or secretions if needed.

- Insert an oral or nasal airway if trained and appropriate.

- Call for help or rapid response if the airway cannot be secured.

Step 2: Breathing — Is the Patient Getting Enough Air?

What to assess:

- Respiratory rate, depth, rhythm

- Chest movement and use of accessory muscles

- Skin color and oxygen saturation (SpO₂)

- Breath sounds: wheezing, crackles, or no air movement

What to do first:

- Apply oxygen if the patient is hypoxic or working hard to breathe.

- Sit the patient upright to expand lung capacity.

- Encourage deep breathing or coughing if they’re awake.

- Use an incentive spirometer post-op if ordered.

- Prepare for assisted ventilation if breathing is severely impaired or absent.

Step 3: Circulation — Is Blood Reaching Vital Organs?

What to assess:

- Pulse rate and strength — weak, bounding, or absent

- Blood pressure

- Skin color and temperature — pale, cool, clammy, or mottled

- External bleeding or signs of internal hemorrhage (abdominal rigidity, low BP, dizziness)

What to do first:

- Apply direct pressure to external bleeding.

- Raise legs slightly if no fractures and patient is hypotensive.

- Start IV access and fluids if ordered.

- Monitor vital signs frequently.

- Start CPR if there is no pulse.

ABC of Nursing Examples: Emergency Room Scenarios

The ER is fast, loud, and unpredictable. That’s why the ABCs are essential — they help you focus on what matters most, even when alarms are beeping and everyone’s talking at once.

Each example follows a simple, logical flow:

What you see → What’s the ABC threat → What to do first

Example 1: Motorcycle Crash with Snoring Sounds

A patient arrives after a motorcycle crash. They’re unconscious, bruised, and making loud snoring sounds while breathing.

- Primary concern: Airway obstruction

- Why it matters: Snoring suggests the tongue or tissue is blocking the airway.

- What to do:

- Use a jaw-thrust to open the airway without moving the neck.

- Suction blood or secretions.

- Call for rapid response and prepare for intubation.

- Use a jaw-thrust to open the airway without moving the neck.

Example 2: Severe Asthma — Can’t Speak Full Sentences

A young adult walks into the ER hunched over, using neck muscles to breathe, and can only speak one or two words at a time.

- Primary concern: Breathing

- Why it matters: The airway is open, but air isn’t moving effectively — respiratory failure is near.

- What to do:

- Apply high-flow oxygen.

- Stay with the patient — do not leave them alone.

- Prepare a nebulizer or bronchodilator treatment.

- Apply high-flow oxygen.

Example 3: Deep Leg Laceration with Rapid Bleeding

A patient walks in alert and talking, but blood is pouring from a deep wound on their leg.

- Primary concern: Circulation

- Why it matters: Airway and breathing are stable, but blood loss can cause shock quickly.

- What to do:

- Apply firm direct pressure.

- Elevate the leg if no fracture is suspected.

- Prepare IV fluids or blood products and notify provider.

- Apply firm direct pressure.

Example 4: Allergic Reaction — Swollen Lips and Wheezing

After eating shellfish, a patient develops lip swelling, wheezing, and trouble speaking.

- Primary concern: Airway narrowing and breathing difficulty

- What to do:

- Administer oxygen.

- Prepare epinephrine, per protocol.

- Keep airway equipment nearby and monitor for a “silent chest.”

- Administer oxygen.

Example 5: Collapse in Waiting Room — No Pulse, No Breathing

A patient suddenly collapses. They’re unresponsive, not breathing, and have no pulse.

- Primary concern: Cardiac arrest — shift from ABC to CAB

- What to do immediately:

- Call a code.

- Start chest compressions.

- Follow CPR sequence: Compressions → Airway → Breathing

- Attach AED as soon as possible.

- Call a code.

ABC of Nursing Examples: Postoperative and Surgical Scenarios

Recovery after surgery can change quickly. A stable patient can develop airway swelling, respiratory depression, or internal bleeding within minutes. That’s why using the ABC nursing assessment post-op is critical — it helps you catch danger before it becomes an emergency.

Example 6: Stridor After Thyroidectomy

A patient is 2 hours post-thyroid surgery. You hear a harsh, high-pitched sound (stridor) when they inhale.

- Primary concern: Airway obstruction from neck swelling or bleeding

- What to do first:

- Stay with the patient — don’t leave the room.

- Call the surgeon or rapid response team.

- Sit the patient upright to ease breathing.

- Prepare for intubation or an emergency tracheostomy.

- Stay with the patient — don’t leave the room.

Example 7: Opioid-Related Respiratory Depression

A post-op patient received IV morphine. Now they’re very drowsy, and their respiratory rate is 8 breaths per minute.

- Primary concern: Breathing is too slow to maintain oxygenation

- What to do first:

- Try gentle stimulation (“take a deep breath”).

- Apply oxygen if SpO₂ is low.

- Stop additional opioid meds.

- Notify the provider and prepare to administer naloxone if ordered.

- Continue to monitor breathing closely.

- Try gentle stimulation (“take a deep breath”).

Example 8: Possible Internal Bleeding After Surgery

A post-op patient looks pale, restless, and says, “I don’t feel right.” Their blood pressure is 88/50, and pulse is increasing.

- Primary concern: Circulation — possible internal hemorrhage

- What to do first:

- Check pulse, BP, skin color, and level of consciousness.

- Call the provider or rapid response team immediately.

- Prepare for IV fluids or blood transfusion.

- Keep the patient flat or slightly elevated — avoid sitting upright if hypotensive.

- Check pulse, BP, skin color, and level of consciousness.

Example 9: Vomiting While Drowsy from Anesthesia

A groggy post-op patient starts vomiting while lying flat.

- Primary concern: Airway protection — risk of aspiration

- What to do first:

- Turn the patient onto their side.

- Suction the mouth if needed.

- Raise the head of the bed when safe.

- Continue monitoring breathing and oxygen levels.

- Turn the patient onto their side.

Example 10: Chest Tube Patient — Sudden Shortness of Breath

A patient with a chest tube after lung surgery suddenly becomes short of breath and reports chest pain.

- Primary concern: Breathing — possible pneumothorax or tube obstruction

- What to do first:

- Check respiratory rate, lung sounds, and oxygen saturation.

- Inspect the chest tube system for kinks or disconnection.

- Apply oxygen.

- Notify the surgeon or rapid response team immediately.

- Check respiratory rate, lung sounds, and oxygen saturation.

Why this matters:

Post-op patients may not always show dramatic symptoms at first. Subtle changes — restlessness, drowsiness, stridor — can be the body’s first warning sign. ABC assessment helps you act before vital signs crash.

ABC of Nursing Examples: Pediatric Scenarios

Children can compensate for a while and then decline suddenly, especially with airway or breathing problems. ABCs prevent hesitation and help nurses act quickly — even when symptoms are less obvious than in adults.

Example 11: Toddler Choking on a Toy

A 3-year-old begins coughing and gasping while playing with small toys. Their face turns red, and they can’t speak.

- Primary concern: Airway obstruction

- What to do first:

- Encourage coughing if air is still moving.

- If unable to cough or breathe — perform abdominal thrusts (Heimlich) if over 1 year old; back blows and chest thrusts if under 1.

- Call for emergency help if choking continues.

- Do not sweep the mouth blindly.

- Encourage coughing if air is still moving.

Example 12: Croup — Barking Cough and Stridor at Rest

A child shows a barking cough and audible stridor even when resting.

- Primary concern: Airway swelling

- What to do first:

- Keep the child calm — crying worsens swelling.

- Sit them upright.

- Provide humidified oxygen or cool mist.

- Prepare for nebulized epinephrine or corticosteroids as ordered.

- Monitor closely for “silent chest” or fatigue.

- Keep the child calm — crying worsens swelling.

Example 13: Bronchiolitis in an Infant — Retractions and Nasal Flaring

An infant has rapid breathing, nasal flaring, and seesaw chest movement.

- Primary concern: Breathing — increased work of breathing

- What to do first:

- Suction nasal secretions gently.

- Provide humidified oxygen if SpO₂ is low.

- Keep infant in upright or caregiver’s arms.

- Watch for apnea or falling saturation.

- Suction nasal secretions gently.

Example 14: Dehydration from Vomiting — Weak Pulse and Sunken Eyes

A 5-year-old with ongoing vomiting has dry lips, sunken eyes, and a thready pulse.

- Primary concern: Circulation — risk of hypovolemic shock

- What to do first:

- Check pulse, BP, capillary refill.

- Start oral or IV fluids as ordered.

- Lay child flat with legs slightly raised if dizzy.

- Monitor urine output and vital signs.

- Check pulse, BP, capillary refill.

Example 15: High Fever — But ABCs Intact

A 7-year-old has a temperature of 103°F but is alert, breathing normally, and has warm skin with strong pulses.

- Primary concern: No immediate ABC threat

- What to do:

- Provide antipyretics if prescribed.

- Offer fluids and monitor temperature.

- Educate parents on fever care guidelines.

- Provide antipyretics if prescribed.

Key reminder:

In pediatrics, airway and breathing come before anything — even fever, pain, or crying. A child may look stable one minute and crash the next if oxygenation isn’t maintained.

ABC of Nursing Examples: OB and Maternity Scenarios

In maternity care, both the mother and fetus depend on rapid, accurate assessment. Airway swelling, seizures, respiratory distress, or hemorrhage can appear suddenly. The ABCs help you respond fast and prevent maternal or fetal harm.

Example 16: Postpartum Hemorrhage — Heavy Vaginal Bleeding

A woman is 30 minutes postpartum. Her pad is soaked in under 10 minutes, and blood is pooling beneath her.

- Primary concern: Circulation — risk of hypovolemic shock

- What to do first:

- Perform a firm fundal massage to help the uterus contract.

- Call the provider or rapid response team.

- Apply clean pads and estimate blood loss.

- Prepare IV fluids, oxytocin, or other uterotonic medications if ordered.

- Monitor vitals and level of consciousness.

- Perform a firm fundal massage to help the uterus contract.

Example 17: Eclampsia — Seizure During Labor

A pregnant woman at 36 weeks begins seizing unexpectedly.

- Primary concern: Airway, then breathing — seizure may obstruct airway or stop breathing

- What to do first:

- Turn the patient onto her left side to protect the airway and prevent aspiration.

- Do not place anything in her mouth.

- Administer oxygen.

- After the seizure, reassess airway and breathing.

- Prepare magnesium sulfate as ordered and monitor fetal heart rate.

- Turn the patient onto her left side to protect the airway and prevent aspiration.

Example 18: Amniotic Fluid Embolism — Sudden Collapse

During delivery, a patient suddenly becomes short of breath, turns blue, and collapses.

- Primary concern: Breathing and circulation — respiratory failure leading to cardiac arrest

- What to do first:

- Call a code or activate emergency response.

- Administer high-flow oxygen.

- Initiate CPR if no pulse is detected.

- Assist with airway management and prepare for intubation.

- Call a code or activate emergency response.

Example 19: Shortness of Breath in Late Pregnancy — Stable Vitals

A woman at 38 weeks says she feels breathless when lying flat, but she can speak full sentences and her oxygen levels are normal.

- Primary concern: Mild breathing discomfort — no immediate ABC threat

- What to do:

- Help her sit upright.

- Encourage slow breathing and reassure her.

- Monitor vitals and continue assessing other patients whose ABCs may be compromised.

- Help her sit upright.

Example 20: Shoulder Dystocia — Baby’s Head Out, Body Stuck

During childbirth, the baby’s head delivers, but the shoulders do not. Mother is alert and breathing well.

- Primary concern: Mother’s ABCs are stable — but baby’s airway will soon be at risk if delivery is delayed

- What to do first:

- Assist the provider with McRoberts maneuver (knees to chest).

- Apply suprapubic pressure if instructed.

- Do not apply fundal pressure.

- Speak calmly to the mother and prepare for possible neonatal resuscitation.

- Assist the provider with McRoberts maneuver (knees to chest).

Key reminder in maternity care:

The mother’s ABCs always come first. If the mother becomes unstable, both she and the baby are at risk. Once her airway, breathing, and circulation are secure, focus shifts to fetal safety.

ABC of Nursing Examples: Mental Health and Medical-Psych Scenarios

Mental health crises can mask real medical emergencies. ABCs prevent you from overlooking physical danger while managing emotional distress.

Example 21: Panic Attack — “I Can’t Breathe” but Talking Clearly

A patient is crying, hyperventilating, and says they can’t breathe — but they’re speaking full sentences and oxygen saturation is 98%.

- Primary concern: Breathing discomfort, not airway failure

- What to do:

- Stay calm and speak in a steady, reassuring voice.

- Encourage slow breaths — inhale through the nose, exhale through the mouth.

- Avoid using paper bags (no longer recommended).

- Continue to monitor airway and respiratory status.

- Stay calm and speak in a steady, reassuring voice.

Example 22: Self-Harm Attempt — Wrist Lacerations with Bleeding

A patient is alert but has deep wrist cuts and steady bleeding.

- Primary concern: Circulation

- What to do:

- Apply direct pressure to control bleeding.

- Elevate the arm if safe.

- Call for medical assistance or rapid response.

- Once stable, shift to psychological safety and suicide precautions.

- Apply direct pressure to control bleeding.

Example 23: Opioid Overdose — Unresponsive, Slow Breathing

A patient is unresponsive after suspected overdose. Respirations are 6 per minute and oxygen saturation is dropping.

- Primary concern: Breathing, then airway

- What to do:

- Try verbal or physical stimulation (sternal rub).

- Open the airway and apply oxygen.

- Prepare naloxone if ordered and within scope.

- Monitor for vomiting or aspiration risk as they wake up.

- Try verbal or physical stimulation (sternal rub).

Example 24: Aggressive Behavior — Threatening Staff, Stable Vitals

A patient is shouting, pacing, and threatening staff. Breathing is normal and no physical injury is visible.

- Primary concern: No ABC threat — behavioral safety issue

- What to do:

- Maintain safe distance and call for help if needed.

- Use calm, non-confrontational communication.

- Prepare for medication or restraints per facility policy.

- Continue monitoring for physical distress.

- Maintain safe distance and call for help if needed.

Example 25: Chest Tightness in a Patient with Schizophrenia

A patient with schizophrenia reports crushing chest pain. They are breathing quickly and look flushed.

- Primary concern: Possible breathing or cardiac circulation issue

- What to do:

- Assess airway and breathing first.

- Ask about pain location, duration, and radiation.

- Take vital signs (BP, pulse, respirations, SpO₂).

- If cardiac origin is suspected — apply oxygen, notify provider, prepare ECG.

- Never assume chest pain is “just anxiety.”

- Assess airway and breathing first.

Takeaway:

Even during psychiatric emergencies, you treat the body before the mind. ABCs always come before emotional care or behavioral intervention.

ABC Nursing Assessment Checklist (Step-by-Step Guide for Quick Decisions)

The ABCs aren’t just something nursing students memorize — they’re the exact steps nurses use when a patient suddenly deteriorates or “just doesn’t look right.” This mini training section helps you move from knowing the ABCs to actually using them confidently in real situations.

This mental checklist keeps you calm and focused, even when alarms are going off and a room is full of people shouting instructions.

How to Document ABC Findings in Nursing Notes

Good documentation protects your license, communicates clearly with the healthcare team, and shows you followed proper priorities.

Here’s an example of short, effective charting using ABC structure:

- “A: Airway patent, patient speaking in full sentences.”

- “B: Respiratory rate 22, SpO₂ 94% on room air.”

- “C: BP 110/70, pulse 88, skin warm and dry, no active bleeding.”

Keep it objective. Keep it quick. Record only what you can see, hear, or measure.

ABCs vs Other Nursing Prioritization Models

The ABCs are the foundation of emergency nursing care — but they’re not the only framework you’ll use. Depending on the situation, you may need to expand to ABCDE, shift to CAB in CPR, or layer in Maslow’s hierarchy to guide non-emergency priorities.

ABCs vs ABCDE (Disability & Exposure Added)

ABCDE builds on the ABC method to assess trauma and critically ill patients more completely.

After Airway, Breathing, and Circulation, continue with:

D – Disability

- Quick neurological check: level of consciousness, pupils, limb movement, or response to pain.

E – Exposure/Environment

- Fully expose the patient to check for hidden injuries, bleeding, or rashes.

- Prevent hypothermia with warm blankets.

When to Use ABCDE

- Trauma patients (motor vehicle accidents, falls, assaults)

- ICU or emergency department settings

- Rapid response situations when more than breathing and circulation are involved

The key rule still applies: never move to D or E until A, B, and C are stable.

ABCs vs CAB (Compressions–Airway–Breathing in CPR)

In most situations, you follow ABC. But if the patient has no pulse and no breathing, cardiac arrest protocols switch the order to CAB.

CAB means:

- Compressions — Start chest compressions immediately.

- Airway — Open the airway after compressions begin.

- Breathing — Give rescue breaths or use a bag-valve mask.

When CAB Applies

- Cardiac arrest

- No pulse and no breathing present

- Following American Heart Association (AHA) CPR guidelines

So, remember:

If the heart stops, start with C — not A.

ABCs + Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow helps with overall patient care, but ABCs always come first when survival is at risk.

Nursing triage logic looks like this:

- Airway, breathing, and circulation always come before pain, teaching, medication questions, or comfort needs.

- Once ABCs are stable, then you move to safety, pain control, emotional care, and education.

Example:

A patient with 10/10 pain waits while you help a patient with chest tightness and difficulty breathing. Pain matters — but oxygen matters more.

FAQs

What does ABC stand for in nursing?

ABC stands for Airway, Breathing, and Circulation.

It’s a life-saving assessment method nurses use to identify and treat the most dangerous problems first. If a patient can’t breathe or has no pulse, teaching, pain medication, or wound care can wait.

When do I use ABC vs. CAB?

- Use ABC for most emergency assessments, trauma situations, or prioritization questions.

- Use CAB (Compressions–Airway–Breathing) only during cardiac arrest, when a patient has no pulse and no breathing.

Can ABCs be used in mental health emergencies?

Yes. Even in psychiatric settings, you always check airway, breathing, and circulation first. A panic attack, overdose, or violent behavior can become life-threatening quickly. Emotional support comes after physical stability.

How do I practice ABCs for nursing exams?

- Use NCLEX-style questions and ask: “Which problem threatens life first?”

- Practice identifying airway obstruction, respiratory distress, and shock.

- Use flashcards or quick case scenarios, and say the priorities out loud.

- Do mock simulations or group practice in skills lab to build confidence.

Conclusion

Whether you’re working in the ER, pediatrics, maternity, mental health, or long-term care — one rule never changes: you always start with ABC. It’s the foundation of safe nursing practice and the quickest way to prevent avoidable death.

When things feel chaotic or overwhelming, go back to the basics:

- Airway — Is it open?

- Breathing — Is oxygen moving in and out?

- Circulation — Is blood getting that oxygen to vital organs?

This guide showed how the ABC nursing assessment applies across real scenarios — from choking toddlers and postpartum hemorrhage to drug overdose and trauma. No matter how complex the situation seems, ABCs help you focus on what will kill the patient first if left untreated.

So keep practicing. Use:

- Real-case simulations

- Flashcards with ABC nursing examples

- NCLEX-style questions

- Peer or lab practice sessions

Build the habit now so that when a patient can’t breathe, is bleeding out, or suddenly collapses — your response is automatic, calm, and correct.

Because once you master ABCs, you’re not just remembering steps.

You’re learning how to save a life.